By Laura Grimes

Today is the last day of National Poetry Month. Tomorrow is the one-year anniversary of my last day at a large daily news organization. So it seems only fitting to reimagine a new, inspiring era of journalism … that incorporates poetry.

*****

For more than half my life I was a journalist. At least that’s the occupation I wrote on insurance applications and medical forms. But in the beginning it just seemed like one paycheck away from my real occupation: a big liberal arts question mark.

When I was fresh out of college and looking for work I vowed I would never work for a newspaper. I hated being pressed to finish term papers, why would I subject myself to deadlines every day? But I loved the whole messy process of publishing and had ever since I walked into Mrs. Wallis’ yearbook class my junior year of high school. The pull was still strong. After college, a quick accounting of publishing job options revealed:

- Literary magazines, tops on my list at the time, had no paycheck.

- Glossy magazines meant moving to New York.

- Book publishing ditto.

- Leaving the idea of working for a large daily newspaper really appealing.

So at a once-large publishing company in Portland, Oregon, my love affair with newspapering began, slowly at first, but eventually growing into a deep passion. The job taught me to work with speed and economy.

Continue reading Journalism and poetry: Is a new romance in the air?

Howard is one of the founders of the story theater, and so it was fitting that his hour-long piece, The Adventures of Huckleberry Horowitz, kicked the festival off. Most everyone knows the mystical power of chicken soup, and most understand the pull of ritual and tradition in that thing we loosely call religion, so Howard’s audience, maybe 65 or 70 strong, rippled into laughter: the easy, familiar kind, the kind that says, “Yeah, we know what you mean.”

Howard is one of the founders of the story theater, and so it was fitting that his hour-long piece, The Adventures of Huckleberry Horowitz, kicked the festival off. Most everyone knows the mystical power of chicken soup, and most understand the pull of ritual and tradition in that thing we loosely call religion, so Howard’s audience, maybe 65 or 70 strong, rippled into laughter: the easy, familiar kind, the kind that says, “Yeah, we know what you mean.” I put my bag on the floor and moved a portable potty out of the way to give her a sideways hug.

I put my bag on the floor and moved a portable potty out of the way to give her a sideways hug.

I am more than a little envious that he got this assignment. I’m the one who’s had my eye on this show for months. I’m the one who

I am more than a little envious that he got this assignment. I’m the one who’s had my eye on this show for months. I’m the one who  “Excuse me?” I said. “You got to meet him?”

“Excuse me?” I said. “You got to meet him?” “Rose’s life sometimes seems too exemplary to be true,” Nightingale writes. “Add some convenient coincidences to her tale — like meeting a bitter old shopkeeper in the Arizona desert and realizing he is the spouse she thought she had lost to Dachau — and Rose could easily be a case study rather than a character.”

“Rose’s life sometimes seems too exemplary to be true,” Nightingale writes. “Add some convenient coincidences to her tale — like meeting a bitter old shopkeeper in the Arizona desert and realizing he is the spouse she thought she had lost to Dachau — and Rose could easily be a case study rather than a character.” Ms. Alsop is

Ms. Alsop is  In

In  In 1963 I had the honor of hosting Auden, who was giving a reading at a community college I attended at the time. There was a dinner and reception before the reading, during which he drank, by my own nervous count, a dozen martinis! And seemed drunk. We didn’t know what to do, and when approached he assured us all was fine, no, he didn’t want any coffee …. so off we went to the reading, nervous as hell. He still seemed drunk to me when he went to the podium. Then somehow he didn’t. He gave a brilliant, flawless reading. Then he stepped away, seemed drunk again, and wanted to know when he could have a drink.

In 1963 I had the honor of hosting Auden, who was giving a reading at a community college I attended at the time. There was a dinner and reception before the reading, during which he drank, by my own nervous count, a dozen martinis! And seemed drunk. We didn’t know what to do, and when approached he assured us all was fine, no, he didn’t want any coffee …. so off we went to the reading, nervous as hell. He still seemed drunk to me when he went to the podium. Then somehow he didn’t. He gave a brilliant, flawless reading. Then he stepped away, seemed drunk again, and wanted to know when he could have a drink. It’s the latest in Eric Hull‘s

It’s the latest in Eric Hull‘s  Waterbrook is basically a room with an entrance area and a door leading to what serves as a green room for the performers. Somewhere around the corner, down a broad-plank floor, is a restroom. On Saturday the performance space had a few rows of folding chairs for the spectators, a lineup of music stands up front for the six performers, and three chairs to the side for the performers who occasionally sat a poem out. In other words: all the tools you really need to create some first-rate performing art.

Waterbrook is basically a room with an entrance area and a door leading to what serves as a green room for the performers. Somewhere around the corner, down a broad-plank floor, is a restroom. On Saturday the performance space had a few rows of folding chairs for the spectators, a lineup of music stands up front for the six performers, and three chairs to the side for the performers who occasionally sat a poem out. In other words: all the tools you really need to create some first-rate performing art. So it is with heightened interest that Mr. Scatter notes the opening of Keep Portland Beard, an exhibition of hairy art that opens Monday at

So it is with heightened interest that Mr. Scatter notes the opening of Keep Portland Beard, an exhibition of hairy art that opens Monday at  He recalls the story, perhaps apocryphal, about

He recalls the story, perhaps apocryphal, about

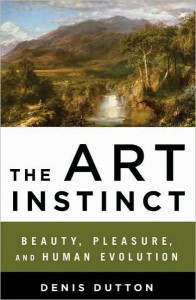

The Art Instinct talks a lot about the evolutionary bases of the urge to make art: the biological hard-wiring, if you will. Dutton likes to take his readers back to the Pleistocene era, when the combination of natural selection and the more “designed” selection of socialization, or “human self-domestication,” was creating the ways we still think and feel. To oversimplify grossly, he takes us to that place where short-term survival (the ability to hunt; a prudent fear of snakes) meets long-term survival (the choosing of sexual mates on the basis of desirable personal traits including “intelligence, industriousness, courage, imagination, eloquence”). Somewhere in there, peacock plumage enters into the equation.

The Art Instinct talks a lot about the evolutionary bases of the urge to make art: the biological hard-wiring, if you will. Dutton likes to take his readers back to the Pleistocene era, when the combination of natural selection and the more “designed” selection of socialization, or “human self-domestication,” was creating the ways we still think and feel. To oversimplify grossly, he takes us to that place where short-term survival (the ability to hunt; a prudent fear of snakes) meets long-term survival (the choosing of sexual mates on the basis of desirable personal traits including “intelligence, industriousness, courage, imagination, eloquence”). Somewhere in there, peacock plumage enters into the equation.