David Cooper/OSF

David Cooper/OSF

By Bob Hicks

The central problem for modern audiences in Shakespeare’s “problem play” Measure for Measure is this: Why doesn’t Isabella just give up her virginity to save her brother’s life? Offensive and transgressive as it would be — what the power-abusing Angelo essentially proposes is mercy at the price of rape — how, in a world of situational ethics, is that a greater harm than allowing her brother to be executed when she could have saved his life? And why, subsidiarily, is Isabella then looked on as such a paragon of virtue that Vincentio, the wise and just Duke of Vienna, proposes at the end of the play to marry her himself? Is she not, by valuing mere chastity over a supposedly beloved brother’s life, the play’s true monster?

Problem, indeed.

I find the suggestion of an answer in The Embarrassment of Riches, Simon Schama’s lauded 1987 investigation of Dutch character and culture during that country’s Golden Age, which overlapped and carried beyond Shakespeare’s own Elizabethan/Jacobean times. Schama calls his opening chapter The Mystery of the Drowning Cell, and recounts the story of a system of punishment that may have been used often, or only rarely, or not at all: perhaps it was just a rumor to keep the citizens in line. Prisoners who were too lazy to work, according to several historical reports, were placed in a dank room in Amsterdam that was slowly flooded with water. Their choice was stark: get busy pumping the water out, or drown. Schama casts the story as a crucial metaphor for the Dutch dilemma of the landscape, a physical space that demands constant vigilance if its inhabitants are to keep from being inundated by the waters of the sea: “To be wet was to be captive, idle and poor. To be dry was to be free, industrious and comfortable. This was the lesson of the drowning cell.”

In other words: sometimes extremes mean more than they mean.

Judith H. Dobrzynski passes along

Judith H. Dobrzynski passes along  Jenny Graham/OSF

Jenny Graham/OSF T. Charles Erickson/OSF

T. Charles Erickson/OSF T. Charles Erickson/OSF

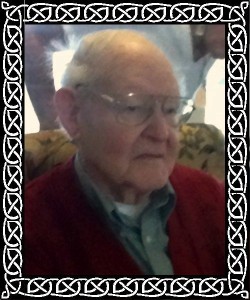

T. Charles Erickson/OSF We pause for a long moment of reflection, love, and respect. Without Irby Hicks there would be no Art Scatter, not just because without him we would never have been born, but also because he instilled in his seven children the love of language and story that is crucial to the forming of any writer. Three of his children became professional writers. The other four are devoted readers.

We pause for a long moment of reflection, love, and respect. Without Irby Hicks there would be no Art Scatter, not just because without him we would never have been born, but also because he instilled in his seven children the love of language and story that is crucial to the forming of any writer. Three of his children became professional writers. The other four are devoted readers. I vividly recall the time he put a chicken on the chopping block and lopped off its head. The decapitated bird rose up, flapped its wings, and flew across the low-lying garage, finally flopping to the ground on the other side. One sister recalls this. No one else does. So my sister and I wonder: Was this somebody else’s story that we somehow transposed to Dad? I remember the time I came home from school and encountered a whole hog’s head staring up from the bathtub: Dad had acquired it, and until he had time to strip it down, there was no place else to store it. No one else remembers that one. Did it happen? One thing’s true: the garden. That large, lush garden that for years flourished so magnificently. Maybe I think of food because it nourishes, and Dad nourished my own life. I am, in many ways, what he planted.

I vividly recall the time he put a chicken on the chopping block and lopped off its head. The decapitated bird rose up, flapped its wings, and flew across the low-lying garage, finally flopping to the ground on the other side. One sister recalls this. No one else does. So my sister and I wonder: Was this somebody else’s story that we somehow transposed to Dad? I remember the time I came home from school and encountered a whole hog’s head staring up from the bathtub: Dad had acquired it, and until he had time to strip it down, there was no place else to store it. No one else remembers that one. Did it happen? One thing’s true: the garden. That large, lush garden that for years flourished so magnificently. Maybe I think of food because it nourishes, and Dad nourished my own life. I am, in many ways, what he planted.