By Martha Ullman West

Art Scatter is always pleased as punch to accept an essay from its chief correspondent and occasional world traveler, Martha Ullman West. MUW has been a busy woman lately. Herewith we offer her personal recollections of the late, great Lena Horne; her thoughts on the swan song of dancer Gavin Larsen, retiring from Oregon Ballet Theatre (plus other thoughts about OBT); Cedar Lake Contemporary Dance; and a comic theatrical riff on the Bronte sisters. Whew: That covers some territory!

First and second thoughts on a Monday morning —

I was going to start this post with some second thoughts about Oregon Ballet Theatre‘s recent Duets concert series and specifically last Sunday’s matinee performance, Gavin Larsen‘s last as a principal dancer.

But I logged on to my e-mail an hour or so before I began writing and found that a high school classmate had forwarded me the New York Times obituary for Lena Horne, so I’ll start with some extremely vivid memories of her that go back, oh dear God, 58 years.

Her daughter, Gail Jones, was a year ahead of me at a Quaker boarding school in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., called Oakwood. The glamorous Lena Horne was a loving, devoted mother, who always came to Parents Day — and so did my father, believe you me.

Her daughter, Gail Jones, was a year ahead of me at a Quaker boarding school in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., called Oakwood. The glamorous Lena Horne was a loving, devoted mother, who always came to Parents Day — and so did my father, believe you me.

First memory: October of my freshman year, Lena in a red velvet suit, prowling (no other word for it) along the football field, definitely deflecting fatherly attention from the game as well as the nubile cheerleaders, although Dad claimed for years he heard a Quaker referee calling “Thee is out.”

Second memory: Two years later, a cold wintry day, I was running barefoot down the hall of my dormitory when that unmistakable voice called from Gail’s room, “Child, put your shoes on — it’s freezing in here.” I stopped dead in my tracks, turned around, and there she was; looking, needless to say, stunning. And stern. I put my shoes on.

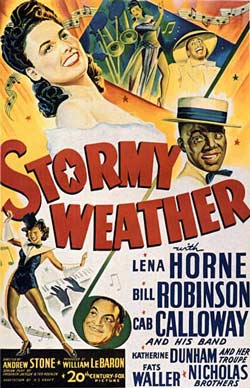

Third memory: The American Masters PBS show twelve years ago in honor of her 80th birthday (and she looked about 50, I might add), which I imagine PBS will reprise and I urge all Scatterers to watch. Daughter Gail Jones’s history of the Horne Family is also well worth reading. As is the Times obituary. Lots of “Stormy Weather” in Lena’s life; damned if she did, damned if she didn’t, and did she ever overcome, with astonishing glamor and grace.

*

There was plenty of grace of a different kind, and glamour best described as casual, as Oregon Ballet Theatre’s dancers filed past Larsen at the second intermission a week ago Sunday. Larsen was still in her Duo Concertant practice clothes costume, crowned with a ballerina’s tiara. The casual part applies to the jeans-clad dancers who each gave her a single rose and a kiss as they walked past her: It’s a tradition that began, I believe, at the Paris Opera Ballet.

As Larsen took bow after bow, she was showered with more roses that came swooping down from the balconies at the Newmark. Each was well-earned in a long career that culminated not only in a superb performance by her that day in Tolstoy’s Waltz and Duo Concertant, but also by her colleagues — Anne Mueller and Chauncey Parsons, who nailed Twyla Tharp’s Known by Heart duet, and looked like they were having the time of their lives executing its mixed metaphors; Kathi Martuza in everything she danced, but especially Like a Samba; and Lucas Threefoot repeating his blast-off rocket of a performance in the male solo Saturday night. (I knew that boy was going far, and I just hope he stays here while he does it).

As Larsen took bow after bow, she was showered with more roses that came swooping down from the balconies at the Newmark. Each was well-earned in a long career that culminated not only in a superb performance by her that day in Tolstoy’s Waltz and Duo Concertant, but also by her colleagues — Anne Mueller and Chauncey Parsons, who nailed Twyla Tharp’s Known by Heart duet, and looked like they were having the time of their lives executing its mixed metaphors; Kathi Martuza in everything she danced, but especially Like a Samba; and Lucas Threefoot repeating his blast-off rocket of a performance in the male solo Saturday night. (I knew that boy was going far, and I just hope he stays here while he does it).

In Divergence, Martuza and the other dancers were so damned good they made me forget about the set piece and the dreary score. In fact, all the dancers, (though this, alas, was not the whole company: Those on short contracts return, thank God, for the June show) danced their hearts out in everything they performed at that Sunday mat, and we in the audience were honored to be present.

Back to Tolstoy’s Waltz, a piece I enjoy more every time I see it, and about which I must now eat a bit of braised crow (I prefer it cooked slowly in a good red wine, plucked). Sometimes critics, especially if we’ve been at it for a long time, bring too much context to a performance.

The duet I reviewed as a send-up of Russian soul, having seen Artur Sultanov perform it on opening night partnering Martuza, I learned quite by accident from Christopher Stowell (who should know; he created it) is a serious piece about an abusive husband mistreating his blind wife. The other thing I thought he might be satirizing (and here comes the ballet history context) is Balanchine’s La Somnambula, an early, rather opaque, and sometimes overblown work. That context I had erased from my embarrassed mind when I watched Larsen and Adrian Fry perform it on Sunday afternoon, in a rendering laced with menace and fear.

It also occurred to me that casting is everything: Sultanov, who is a wonderful comedian (more mistaken context) is also such a sweet man, I think it’s hard for him to look abusive on stage. Creepy, yes, but not brutal. Fry, who we are losing to Ballet West next season, looked extremely threatening — even sadistic — and Larsen, her wavy hair streaming down her back, vulnerability and dread emanating from every muscle in her body, brought me close to tears.

*

Having said all that, I think a knowledge of ballet history served me well as an audience member at Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet‘s performance at the Schnitz last Wednesday, the final show in White Bird‘s 2009-10 season and, except for Mikhail Baryshnikov and Anna Laguna at the Newmark last fall, arguably the best. (I must exclude Hubbard Street Dance Chicago, substituting for Lyon Opera Ballet, from this assessment, because I was watching bad belly dancing on the Nile when they were here. And I’m not talking about White Bird Uncaged, either.)

In this White Bird season we have seen, God knows, superb dancers, beautifully trained technically, with gorgeous bodies, generally speaking costumed minimally to show off those ditto bodies, but the choreography has frequently been wanting. Explosive, yes indeed. Virtuosic, absolutely. But nuanced and detailed? Seldom.

Each show has had some interesting moments, some have had a few that were highly offensive, (Martha Graham’s Lamentation imitated by the dancers from Complexions Contemporary Ballet seated on upside-down buckets in Dwight Rhoden’s Mercy comes to mind) but in Cedar Lake’s show, fantastically good dancing of by and large interesting and innovative choreography made me hope White Bird brings them back soon.

I expected Crystal Pite’s Ten Duets on a Theme of Rescue to knock my socks off, and it did. Her company, Kidd Pivot, did just that one rainy night at Reed College when it performed as part of White Bird Uncaged, last year I think.

But the pleasure I took in viewing Jo Stromgren’s Sunday Again was an agreeable surprise, and that’s where having some context comes in. We are informed in the program notes (which I read for the first time five minutes ago), that the piece is about the music (Bach’s oratorio Jesu, Meine Freude, and the alternately silky and rubbery movement, some of it simple, some of it elaborate, certainly bears witness to that) and also about “the domestic jungle of luxury problems and gender frictions,” whatever the hell that means. Although there was a fine British film with Glenda Jackson several eons ago called Sunday Bloody Sunday that could have been written about in those terms.

What the piece seemed to me to echo, and elaborate on, is Nijinsky‘s Jeux, said to be inspired by a tennis match in the garden of Lady Ottoline Morrell’s home in London’s Bedford Square, and his sister Nijinska‘s Les Biches, which is about a house party that takes place in France, and the outre misbehavior of hostess and guests, including the suggestion of a lesbian affair. It’s an extremely funny and sophisticated piece, and Sunday, Again can’t even touch it for those attributes, but the groping search for the missing badminton shuttlecock by one woman through another’s clothes (real clothes, trousers, dresses; what were they thinking in the age of just wear toe shoes and a Jantzen, I ask?) seemed to me to be a satirical take on choreography in the earlier work. In fact, I enjoyed the movement in this piece, as well as the eloquent lighting design and the changes of tone and pace so much I really didn’t want it to end.

Equally varied in tone and pace, but with very different movement from Sunday, Again, Dutch choreographer Didy Veldman’s Frame of View was as visually fascinating as a Fellini film, with considerable surrealism in both the set (a series of doors that opened and shut, facilitating transitions between various duets and solos) and the costumes — I especially loved a man’s suit that made him look like a well-tailored circus clown. And the slam-bang cafe table duet performed to Jacques Brel’s Ne Me Quitte Pas (“Don’t Leave Me,” and there is no s’il vous plais in the title or the song) was a perfect choreographic illustration of the dangers of scorning a woman in love. Both Sunday, Again and Frame of View deal with some reasonably serious issues, namely human relationships, human angst, human frailty; but both choreographers understand, it seems to me, that you can make a dance about those things without being ponderous or pedantic, and even — what a concept! — give the audience some laughs. Shakespeare, who knew a thing or two about eliciting emotional response, always produced some comic bits in his tragedies, which is why it’s called comic relief.

*

Finally, I strolled over to Tabor Space, a wonderful new performance space in Mt. Tabor Presbyterian Church on Belmont, on Mother’s Day to take in the last performance of Withering Looks, British writers Maggie Fox and Sue Ryding’s hilarious riff on the basically tragic lives of the motherless Bronte Sisters: Emily, whose Wuthering Heights has caused floods of bitter tears to be shed by several generations of women; and Charlotte, whose Jane Eyre I read for the first time at the age of 10, and most recently at, um, 60. I intend to read it again. A third sister, Anne, was also a novelist; she appears in Withering Looks as a doll, gone but not so to speak forgotten. Emily died young, as did Anne, and in today’s terms, so did Charlotte, having achieved enormous success with Jane Eyre and lesser success with several other novels, which are also very good, who got out of the parsonage and got married, only to die at 39, in childbirth.

The writing in Withering Looks, which makes use of some reiterations of Sister Emily on the subject of the moors, is superb. Vana O’Brien as Emily and a range of secondary characters, and Luisa Sermol as Charlotte and some more secondary characters (Heathcliff among them), deliver their lines with perfect timing in impeccably accented Britglish. No surprise there. My Friend the Choreographer (aka Gregg Bielemeier) put together some self-described silly little dances; his pitch for comedy is as perfect as O’Brien’s and Sermol’s, as well as Louanne Moldovan’s, the director of this enterprise.

Context, that of having read these novels, wasn’t actually necessary for the enjoyment of this show — my next door neighbors, who hadn’t read them, went with me, and were deeply appreciative, laughing heartily throughout. There are myriad ways to perceive good theater and dancing, of which we’ve had one hell of a lot in the past couple of weeks.

*

ILLUSTRATIONS, from top:

— Cropped screenshot of Lena Horne from “Till the Clouds Roll By,” 1946. Wikimedia Commons

— Original poster from Lena Horne’s 1941 movie “Stormy Weather.” Wikimedia Commons

— Gavin Larsen, resplendent in George Balanchine’s “Duo Concertante.” Photo: Blaine Truitt Covert/Oregon Ballet Theatre