Like so many great art forms, dance is a series of interlinked relationships and memories, a tradition that continually redefines and reinvents itself. It lives in the past, and the present, and the future, and its story is written in the memories and associations of open-hearted observers as well as the muscles of dancers and the patterns in choreographers’ minds.

Dance writer Martha Ullman West, one of our best observers, took in last Friday’s Dance United, and for her it was like biting into a madeleine: The reminiscences and connections just began to flow. Somehow, no matter how far-flung, they all looped back to Oregon Ballet Theatre, its history and successes, and this extraordinary event to keep the company alive and vital.

Here is the link to Martha’s review in The Oregonian of the performance. And here, below, is her more personal report on what it all meant:

———————————————————————-

Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans.

Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans.

Dancers came from Texas, Utah, Massachusetts, Canada, Washington state, California, Chicago, Idaho, and that other geographical location, in New York called Downtown, here designated as Portland’s modern and contemporary dance community.

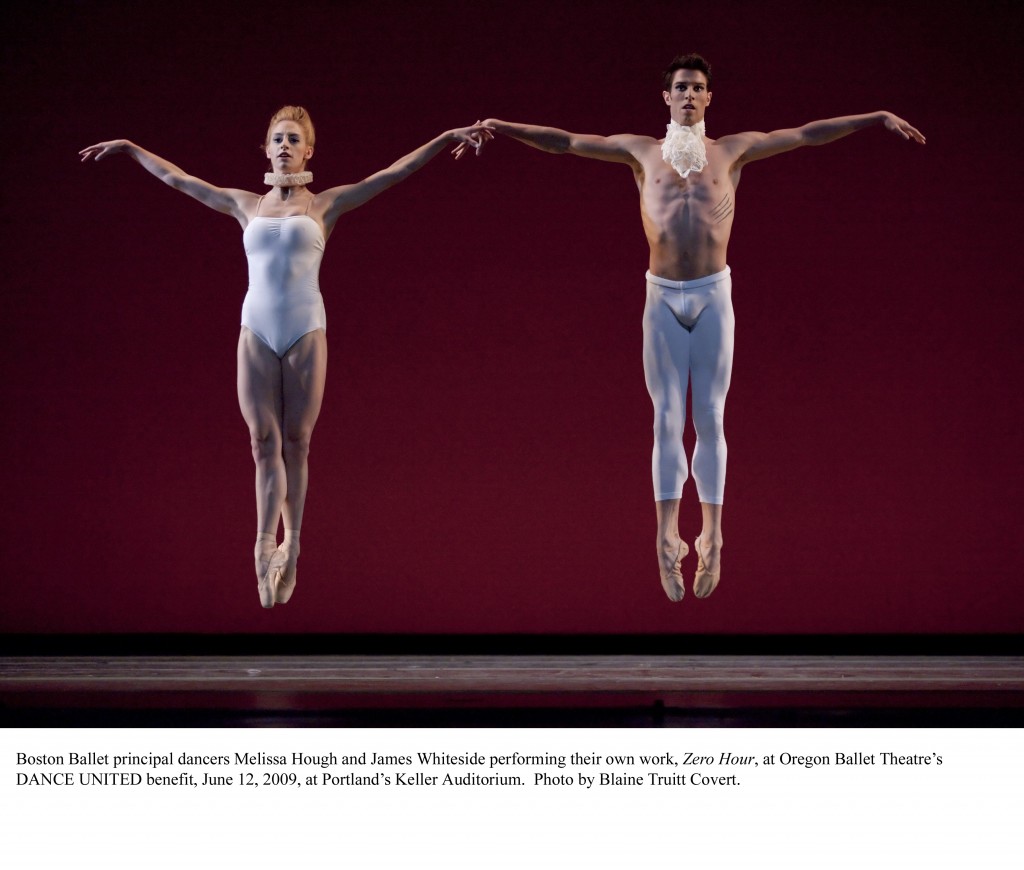

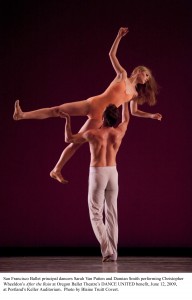

The gifts they brought were generous: their talent and their time. And they were welcomed to Keller Auditorium with the same enthusiasm as Obama’s supporters do and did, reaching into their wallets with many relatively small donations to keep Oregon Ballet Theatre alive. On Tuesday, OBT had in hand $720,000 of the $750,000 it needs to make up THIS season’s deficit.

I’ve been watching dance in Portland and elsewhere for more decades that I wish to reveal, and professionally since 1979, when I wrote an essay on postmodern dance in New York for Dance Magazine. In so many ways, this gala triggered some Proustian moments, also making me think of all the ways that dance and dancers are connected to each other.

Linda Austin’s thoroughly postmodern “anybody-can-dance, any-movement-on-stage-is-valid” Boris & Natasha Dancers (on catnip) took me back to New York’s SoHo and a performance created by Karole Armitage consisting of a group of dancers on their hands and knees, painting stripes on the floor, in humorless silence. They were not skilled at either painting or dancing, but it was the same democratic approach to the art form as Austin’s new dance, which featured such pillars of the Portland community as two Bragdons (Peter and David), Scott Bricker, James Harrison and Peter Ames Carlin galumphing across the stage, one of them wearing red sneakers that I wondered if he’d borrowed from White Bird’s Paul King. (Armitage, you may remember, also made work on OBT’s dancers on James Canfield’s watch.)

The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

And I thought about Mark Goldweber, ballet master at OBT under Canfield, then for some years at the Joffrey, and now at Ballet West. (He gave the only authentic performance in Robert Altman’s dance film The Company, in my view.) I wondered what Mark thinks about the way Adam Sklute, now Ballet West’s artistic director, staged this version of the White Swan pas de deux.

When I encountered this ballet’s real-life Prince Siegfried, Christopher Ruud, at OBT’s studios earlier in the week, I spoke with him about his father, who had helped Todd Bolender at Kansas City Ballet (Bolender is the subject of a book I’m working on). Ruud told me he had staged one of his father’s pieces on the company several years ago.

And I thought about how Alison Roper, dancing OBT’s full-length Swan Lake, moves me to tears every time she dances it. Which led me to remembering Jacqueline Schumacher, on her feet and cheering when OBT did the second act, only with Stephanie Crank dancing Odette sublimely.

Ballet is woman, Balanchine said, a sexist statement from a man who was an aficionado of women and really, I think, did not intend to demean us. But in the 21st century, ballet is also men, as it never has been before, judging from this gala. Item: John Michael Schert, from the Trey McIntyre Project, in his solo from Leatherwing Bat, performing McIntyre’s difficult blend of ballet and modern, exemplified by a rubbery-legged leap from a tight fifth position. McIntyre has long been linked to OBT and his choreographic career began at Houston Ballet, whose Melody Herrera and Ian Casady performed artistic director Stanton Welch’s Falling, an uncharacteristically lyrical pas de deux.

Ballet is woman, Balanchine said, a sexist statement from a man who was an aficionado of women and really, I think, did not intend to demean us. But in the 21st century, ballet is also men, as it never has been before, judging from this gala. Item: John Michael Schert, from the Trey McIntyre Project, in his solo from Leatherwing Bat, performing McIntyre’s difficult blend of ballet and modern, exemplified by a rubbery-legged leap from a tight fifth position. McIntyre has long been linked to OBT and his choreographic career began at Houston Ballet, whose Melody Herrera and Ian Casady performed artistic director Stanton Welch’s Falling, an uncharacteristically lyrical pas de deux.

The phenomenal performance by the National Ballet of Canada’s Zdenek Konvalina of some of Maurice Bejart’s Seven Greek Dances reminded me that the last time we saw anything of Bejart’s in this town was when Baryshnikov came here with his “friends” in the mid-1980s, presented by Pacific Ballet Theatre, another precursor of OBT. And that reminded me that Baryshnikov will be here in the fall to open the White Bird Season with choreography suited to someone who’s been doing modern dance for the last decade or so.

Baryshnikov, along with Nureyev, is probably responsible for ballet being man as well as woman in America today. Russians have always influenced the ballet audience here, an audience that is hungry (for reasons that frankly elude me) for the kind of pyrotechnics that Kirov Academy-trained OBT dancer Chauncey Parsons provided with a brief divertissement from Don Quixote. He did it well, and definitely knows how to take a bow, as all Russian-trained dancers do.

The ebullient and speedy performance of New York City Ballet’s Daniel Ulbricht in Balanchine’s Tarantella, partnering Megan Fairchild, reminded me that that was one of OBT artistic director Christopher Stowell’s roles in San Francisco. I’ve seen only a clip of him dancing it, but it brought me to my feet in the privacy of my upstairs “media” room. He, of course, is also a member of the Balanchine tribe, as the son of Kent Stowell and Francia Russell and a graduate of the School of American Ballet.

Jeffrey Stanton, from Pacific Northwest Ballet, was developed as a dancer by Stowell and Russell, as was Mara Vinson: They performed the central pas de deux from Balanchine’s Diamonds. I would love to see OBT dancer Grace Shibley in that role one day, preferably dancing with OBT still. But she is so talented, so versatile, and so intelligent, I’m afraid we’ll lose her.

Portland’s modern choreographers are also very much linked to OBT. Jamey Hampton made work for Ballet Oregon and OBT back in the old days, and so did Mary Oslund and Minh Tran, who courtesy of White Bird performed an excerpt from Kiss, featuring dancers who if not for this gala would never have made it on to the Keller stage. It was not ever thus: Portland Dance Theater was the first of the city’s modern dance company’s to dance there, back in the 1970s when it was the Civic Auditorium. I saw them perform a piece called Ear-Heart that I didn’t think much of, though I greatly enjoyed the easy improvisational movement of a dancer named Gregg Bielemeier, performed in a plastic bubble, long before we became friends.

I’ve heard some complaints about Oslund’s duet from her new work, Anatomica, being included in this gala, and much as I dislike the score — particularly as mangled by the Keller’s sound system — I’ll defend its presence on the program on the grounds that Oslund is as skillful with her highly physical, idiosyncratic movement vocabulary as Caniparoli and McIntyre are with theirs. Again, it’s a pity she had to present an excerpt from a longer work. I was much taken with its premiere out at PCC, in a far less appropriate space. She, and Conduit, which she co-directs, are scrambling for support themselves; that makes her contribution to this potlatch pretty significant.

When I first arrived in Portland, in 1964, there was no resident ballet company and I believe there were no truly professional contemporary dancers working here, either. Big ballet companies toured here, including the Royal Ballet, the Harkness Ballet, American Ballet Theatre, and the Joffrey. The Martha Graham Company toured here sometime in the late ’60s or early ’70s. But there was nothing that was our own, although Willam Christensen had tried to establish a professional ballet here in the late ’30s, but left to take over the San Francisco Opera Ballet — taking Jacqueline Martin (who became Schumacher), Janet Reed and a number of other dancers with him.

I thought about that as I watched Dance United, of how rich we are now in dance that reflects various aspects of this community. That community includes a ballet company that, far from emerging on the national scene (sorry former Mayor Katz; wrong word) has taken its rightful place in the panoply of American ballet companies.

We need them all: OBT, BodyVox, Oslund Co, Linda Austin, Minh Tran, Conduit, the Portland Ballet, which wasn’t represented on stage but showed its support by purchasing a full-page ad in the program, and all the other dance groups and independent artists who are valiantly swimming in this Terpsichorean pond, trying to keep their heads above water.

They are all hard-working members of the community, taxpayers, home owners, educators, responsible for lifting our spirits and telling us who we are.