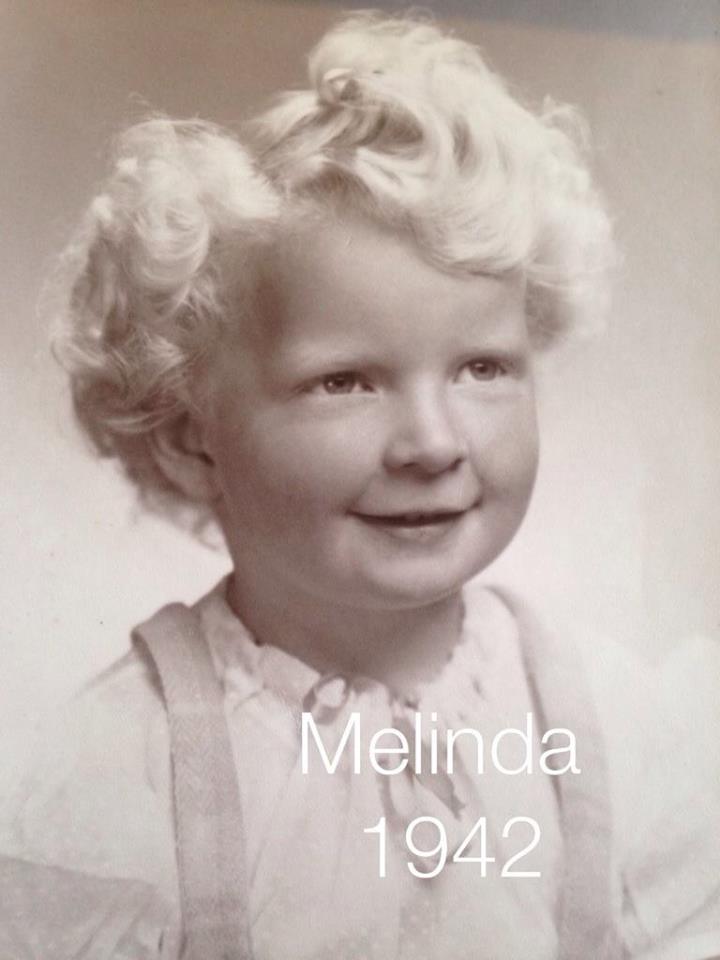

My sister Melinda Louise Lee, born Melinda Louise Hicks on June 7, 1942, in Richmond, California, died on Thanksgiving morning, November 28, 2013, at her Seattle home, while lying in bed and holding her Kindle: as her kids and our sister Barb noted, Lindy loved to read. She died quickly, apparently of a heart attack, and unexpectedly, just six weeks after our mother, Charlotte Lucille Baldwin Hicks, had died at age 93. Mom’s death was a shock but no surprise. Lindy’s was out of the blue, one that no one was prepared for: she was filled with vitality to the end.

Printed below is the text of what I said at Lindy’s memorial service on Friday, December 6, in Ferndale, Washington, where we grew up. Three of Lindy’s children, Melissa Doll, Fernzwood (Bud) Lee Jr., and Kelli Harrell, also spoke. Lindy’s fourth child, Alicia Gudgel, sang. Their messages were beautiful and from the heart. I mentioned before I began my prepared talk that Lindy’s death was devastating, not just because it was unexpected but also because she was in so many ways the heart of our large extended family. And I noted that there were many Lindys lodged in our memories and imaginations, a different Lindy for each of us who knew her. She was the oldest of seven siblings, and four years older than the next-oldest, Laurel. She was five and a half years older than I am, and 11 years older than the next in line, Barb, 12 years older than Chuck, more than 13 older than Bill, and 15 years older than the youngest of us, John. Four years or even 15 in the adult world isn’t a lot: it’s an easy bridge to gap. But in childhood, that’s a chasm, and it can make for vastly different relationships. One of the many wonders about Lindy is that in later life she so easily embraced all of us: it was a reflection of her warmth and generosity of spirit.

Here is a link to her official online obituary.

And here’s my talk.

*

The first thing I want to say is, hardly anyone was more alive than our friend and sister and aunt and mother and grandmother Lindy, and that’s what makes this thing so difficult to understand. It’s like she just disappeared in mid-laugh or mid-sentence, just dropped away, or went into the kitchen to get a glass of water, and hold that thought because she’ll be right back. Except she won’t, and although our minds know that, our hearts can’t quite believe. So now it’s good to remember, because by remembering we keep the warmth and conversations flowing.

Lindy was born with spit and vinegar. And, I think, an innate ability to make mashed potatoes, but we’ll get to that part later. She always knew her mind. As our brother John said, she was “always a source of encouragement and an inspiration in that she experienced more than her share of tragedy and yet remained fully engaged in life.” She was hard-headed as a kid, and she took the brunt of a lot. She was born in 1942 and basically lived alone with Mom until the end of the war, when suddenly this man appeared who it turned out was her father and reclaimed his place in the family, and that was a bit of a shock. And then those new kids started popping out! She had an independent streak five miles long, and I think maybe it came from those war years, when life was sparse but she also had the kind of freedom that war-year kids enjoyed.

That changed. Lindy was curious and gregarious and she wanted to do things, and Dad wanted to keep her protected, and sometimes, as you can imagine, battle royals would break out. “Who were you with? What time did you get home?” There was a place in Bellingham called Shakey’s; I imagine some of you remember it. “I don’t want you going to that pizza joint. They serve beer on the other side.” He hated her music, which was your standard Elvis variety pop ‘n roll, and all she really wanted to do was to be an ordinary late-1950s teenager, which was an exotic sort of beast for a man who came of age in the depths of the Depression. So they fought, and sometimes she lost and sometimes she won, and in the process of staking her independent territory she broke the mold for the rest of us. If things got gradually looser and more permissive around the house, it was partly because Dad had mellowed but partly also because Lindy had won some important tactical victories. And as those teen wars disappeared and their relationship evolved into a genuine adult friendship, Dad and Lindy became very close. They liked and respected each other, a lot, and those two things went hand in hand.

Lindy and I had our scraps, too. As the younger brother, it was my duty to annoy her whenever possible. And as the older sister, it was her duty to be annoyed. She liked a Frankie Laine song, “Moonlight Gambler.” She played it over and over on the record player. And when it came on I’d strut around the house, singing out, “They call me the midnight gander,” and then make a honking goose sound, and she’d stamp her feet, and shout, “Mom! Make him stop!,” and on the most satisfying occasions, she’d stomp out of the room and back to her bedroom.

We were all pretty much in one another’s business in those days; privacy was something you got by going somewhere else. Our little house had only one real bedroom, and the skinny front porch, which I was able to commandeer as my own for a few years, was squeezed into service as sleeping quarters. That meant the front door was right by my bed, and I was aware of pretty much all comings and goings. One night as I lay in bed Lindy came home from a date, and the young man in question, unusually, walked her to the front door. He was a bow-tie-and-sportjacket guy, not her type at all, really, and through the window I could see he could see me lying there. Finally he broke an awkward pause, awkward not just because I was watching but because it seemed fairly obvious that Lindy just wanted to get in the house and be done with it. “I guess this isn’t the best spot in the world if you want a goodnight kiss, is it?” he mumbled, and Lindy said, no, I guess it isn’t, and the door opened, and she swept on through, and I thought, first, you blew it, man, and second, I think I just provided my sister with a perfect excuse to escape. It was, curiously, both a letdown and a point of satisfaction, and I turned over and went to sleep happily.

Lindy (far right) with Mom, Dad, and a passel of sibs.

And that was a long time ago, and still seems fresh. I’m left holding long stories and quick summations. Lindy was the oldest of seven siblings, and the glue and gristle of the clan: quick, whip-funny, the one who got things done. She could be diplomatic when diplomacy was called for, but she was unafraid to call a spade a spade. As my daughter Sarah put it, “She was smart, snarky as hell, and didn’t care what anyone thought about that. She was loud, and kind, and vibrant, and one of many women I’m grateful to have had as models.” Lindy liked the casinos and quick trips to Reno, and loved her family and her friends, many who have been close since their school days. She played a mean game of solitaire, always understanding she was up against tough competition. She loved to cook for a crowd, and liked a glass of wine, and could show a scathing wit when she spotted pomposity on the loose. In many ways, as the oldest of us, she was a second mom. And she was a wonderful, loyal friend who I didn’t see often enough. When our mom died in mid-October, just six weeks before Lindy, she was 93, and it felt like the fullness of her time. I can’t help feeling Lindy didn’t get her allotted years, but I’m grateful for the years she had. As our sister Barb put it, “For me, the grace in Lindy’s premature death is that she was young, healthy and vivacious up to the minute of her death, and she died peacefully in her sleep.” Barb reminded me that Lindy often talked about not wanting to grow frail or lose her memory. “Lindy did NOT want to go there,” Barb said. “I’m happy that she died as she wanted to, but so very sad for us.”

Memories, again. When I was barely entering my teens Lindy got married, and left for the life of a Navy wife in San Diego and Okinawa and the Philippines. She had two daughters, Melissa and Alicia, and then Don died, and then she married Mike, and had a son, Bud, and another daughter, Kelli, and she was the center of her own family. For several years I saw her only in passing. She eventually settled in Seattle, and for many years her home was the gathering place for everyone in the family who lived in Seattle, and also for those of us who visited. She was the host, always with a dog running around. I remember a St. Bernard early on; later the dogs got small and lappish. And, my, she would cook. Thanksgiving, Christmas, whenever. We’d all gather at Lindy’s, and maybe there’d be a ham and maybe there’d be a turkey and you could pretty much rest assured there’d be a mound of mashed potatoes. I think in the Philippines she and Mike had picked up a big round table with a Lazy Susan in the middle, and it was always filled with possibilities, always spinning around, always making stops. Lindy had always cooked, and she favored full flavors, nothing fancy, but pack-it-and-smack-it stuff, which was always memorably good. I remember she was fixing whole meals for the family from the time she was about 12, and I think she saw it both as a duty and an expression of love. She just naturally took command, in the kitchen and in life.

So I got to know her again when we were adults, and I found that I liked her very, very much. I liked her loyalty to her family and work and that group of friends from her high school days. I liked her practicality and her sense of honor. She would forgive and accept a lot of things, but she also made it clear how she thought a person ought to act and be. You should take care of yourself. Don’t ask for handouts. Get off your duff and do something, but think it through before you do it, for crying out loud. If you’re being paid, do the job. She was I suppose a conservative if you want to get political about things, but politics was not naturally where her thoughts and feelings landed. And she was the kind of conservative I like to have around me. She listened, she challenged, she rolled with things, she’d change her mind. She was demanding and opinionated, but she was generous. She knew how to dislike your opinions but like you just the same. I’d call her, really, more a traditionalist, not for any kneejerk reasons but because she believed in old-fashioned individualist values. She was open to new ideas, but she wasn’t keen on throwing out the baby with the bathwater. She was always more concerned about the baby than the water, which could always be replaced.

Lindy with Barb (center) and Mom.

What a friend she could be. I think of all of us brothers and sisters, she was closest to Barb and John. Barb wrote, “One thing Lindy and I shared with each other was our friends. When I was in town, she invited me to meet and spend time with her friends, the high school friends with whom she was still in contact after sixty years, and her former work colleagues, who were such an important part of her life. I attended Lindy’s fiftieth high school reunion as her guest. I went to a number of Sears Christmas parties and luncheons. And Lindy wanted to know my friends and spend time with us, too. She adored my former partner’s centenarian aunt, to the point of saying, when my relationship ended, ‘I hope you get custody of Aunt Muriel.’ Every time I was in Seattle, we visited Aunt Muriel together, took her to lunch and played games together. Muriel loved these times, and she loved Lindy.”

Barb continued: “Over the last decade a comfort developed between Lindy and me that allowed us to drop our pretenses, say what we thought, and be who we were. She became that one special person in my life to whom I could say anything without fear. She didn’t always agree with my opinions or the way I led my life, yet I never felt judged, only greatly cared for. We both understood that at the deepest level, we shared core beliefs that guided our lives and especially the ways we understood and related to people. She understood particularly that beliefs and opinions come from life experience, and behavior always has a reason. Not that she excused people for their behavior – she was as fiercely protective as a mother bear when she felt someone was taking advantage of or using people she loved – but she was always compassionate.”

Her compassion was well-earned. Lindy saw two husbands buried, and much of her life savings disappear. She never forgot coming back stateside after her Navy years in the Pacific and discovering that the world had turned: the country was fed up with Vietnam, and instead of being hailed as heroes, returning soldiers and sailors were met with anger – spit on, she would often recall with an abiding sense of shock. I don’t know what she finally thought about the war itself. But the treatment of the men and women who fought it, and supported those who fought it – and I imagine she counted herself among those latter – disturbed her deeply. It violated her senses of respect and honor and fair play. Still, she didn’t let her losses define her. Brother John said: “She enjoyed her life and what she had been given, when she could easily have become bitter. That’s a lesson she will continue to teach.”

Lindy reflecting; me in the background. Photo: Chuck Hicks

Mostly, I think, I’m going to miss that big loud room-filling laugh, which seemed to me to define so perfectly Lindy’s generosity of spirit and joy in living. While laying down the universal laws of existence as she understood them and firmly believed them to be, she almost always kept her sense of humor. She held opinions on things great and small. The last time we were together, after Mom died just a few weeks ago, Lindy regaled us with a lecture on the proper way to prepare dishes for the dishwasher. You don’t rinse them off beforehand, she said. The dishwashers are built to scrub that stuff away. If you put the dishes in all cleaned off, the dishwasher’s still going to do its scrubbing, and instead of scrubbing off the food that isn’t on the dishes anymore, it’s going to scrub the finish off the dishes. It’s a waste of water, and your dishes are going to get ruined. So for crying out loud, don’t rinse the dishes off. I believe she believed this firmly and unwaveringly. And I believe she also understood the fundamental absurdity of holding such a fervent opinion on such a minor topic, and realized that her realization tumbled the whole thing into the realm of divine comedy, undermining her message so it became yet another giggle in the great and generous joke that was the secret of her life. Though mind you, she was a hundred percent right.

How do we hold onto this? How do we keep this gargantuan spirit from fading away? We remember, and we look ahead. I mentioned to my friend Susannah, who lost her own beloved father recently, that when she died Lindy had been just about to meet her newest grandchild, Charlotte, Bud and Maryam’s newborn daughter, who carries her great-grandmother’s name and her grandmother’s genetic code. Susannah sent me a note: “Charlotte carries Lindy and your mom with her, whether she likes it or realizes it, or not. Those genes! What comes to mind is baggage, and at the airport when that barrage of announcements comes over and over, that you aren’t to leave your bags unattended, or let anyone else give you a package. We are carrying our genetic baggage, and someone else has packed it! All our children, and the children of everyone we know, and we, carry all the stories of our pasts and our physical and mental features. It’s mind-boggling.” Susannah hit “send,” and thought about it, and a minute later hit “send” again. “Mind-boggling and MIRACULOUSLY wonderful,” she wrote.

So, yes, I believe in miracles. So long, Lindy. We’ll be watching for you as Charlotte grows.

The miracle continues: Charlotte and her aunt Melissa. Photo: Chuck Hicks