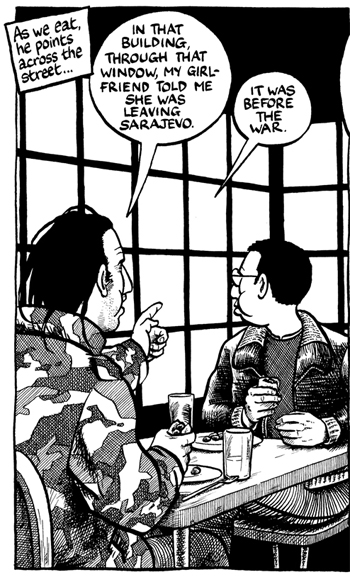

That’s Joe Sacco, to the right, looking out of the window in a restaurant in the old part of Sarajevo. As usual he is passive — listening to the stories that other people tell him, observing life around him and presumably taking notes, though in this frame, he doesn’t seem to have a notebook with him. He looks a lot like a — journalist. Oh. There’s no drawing pad, either. And that’s what usually separates him from other journalists: He is recording conversations,

That’s Joe Sacco, to the right, looking out of the window in a restaurant in the old part of Sarajevo. As usual he is passive — listening to the stories that other people tell him, observing life around him and presumably taking notes, though in this frame, he doesn’t seem to have a notebook with him. He looks a lot like a — journalist. Oh. There’s no drawing pad, either. And that’s what usually separates him from other journalists: He is recording conversations,

observations, scenes AND he’s drawing them.

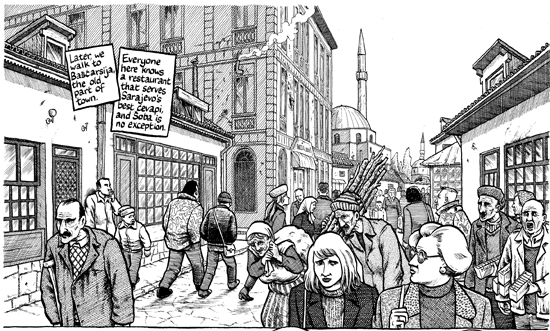

By this particular moment in War’s End: Profiles From Bosnia 1995-96 (2005, Drawn and Quarterly Books), Sacco has drawn and interviewed his subject, Soba, a lot. He’s also drawn the streets of Sarajevo, the insides of clubs and restaurants and apartments. He’s proven to be sympathetic to Soba’s account of his combat against the Serb nationalists attempting to defeat the Bosnian independence movement — he’s listened, he’s drawn, he’s located himself in the narrative. And something wonderful has happened: We’ve gotten to know Soba.

This is still a disorienting experience. From the drawn world, the comics world, we don’t expect the activities of a journalist — the attempt to represent a slice of life as it was actually lived, to make sense of it, to draw conclusions from it. We are just starting to understand, thanks to comics journalists such as Sacco, that the combination of written and drawn representations can be more powerful than the greater abstraction of words alone, that they can convey more fully what the journalist/artist actually found. That they can literally sketch a real character like Soba at the same they “sketch” him.

Our disorientation is apparent in how we categorize books like War’s End — in the graphic novel section of the bookstore, though it’s no more a “novel” than any words-only memoir. This confusion has been pointed out before — see Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics, p. 62, for example. But the profusion of important non-fiction “graphic novels” — which range from personal journalism by Sacco (most famously in Palestine) to coming-of-age autobiography (including Craig Thompson’s Blankets) and beyond — has effectively dynamited the old category.

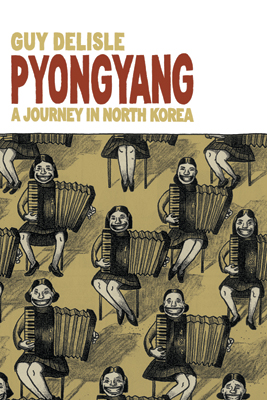

So, what will a closer look at three examples of the “non-fiction graphic novel” tell us, specifically Sacco’s War’s End, Thompson’s Carnet de Voyage (Top Shelf Productions, 2004) and Guy Delisle’s Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea (Drawn and Quarterly Books, 2003)?

1) They give a “true” account of what they witnessed and felt. I don’t mean true in the sense that a novel can be “true” to life. I mean that they explicitly hope to convey what they’ve seen and/or experienced.

2) Their accounts are in first person. We know exactly where they stand in the narrative and in relationship to the people they are representing in text or pictures. Often we can place them literally: Just outside the frame of the drawing, near enough to make out the details we see. Other times, they have drawn themselves into the frames as Sacco did.

3) Their own shifting states of mind figure prominently: They tell us how the way they are feeling or thinking might affect the narratives we are reading/viewing.

4) Although their drawing aims and intensity levels may differ, their visual images are at least as important as the words. In fact, we might be inclined to contest some of the text, knowing what we know about the limits of reporting and interviewing, but the drawings of all three are immediately convincing, despite their different styles. The drawing don’t just convey information, either, they create a felt world for the reader/viewer.

A side-benefit of considering these three books? Travel! Thompson takes us to Europe and Morocco. Delisle heads for North Korea. And for Sacco, it’s the old Yugoslavia. And the places aren’t just background, either, they emerge as independent subjects of their own.

Craig Thompson

O, the fame, the misery

As Carnet de Voyage begins on March 6, 2004, Craig Thompson is 28 and heading for Paris. Blankets, his autobiographical account of growing up in a evangelical Christian household, has been published in the U.S. the previous year, to major acclaim, and his European publishers want him to do a promotional tour for a couple of months, signing books for fans, meeting other comics artists, attending some big continental comics fests. Most, if not all, paid for by the publishers and convention organizers. Sweet! To be young, gifted, single and comped on a European vacation. He even has a side trip scheduled for Morocco. The Carnet is his sketchbook diary of that trip, and we might expect it to be a celebration, maybe even a bacchanal!

Except that maybe we’ve read Blankets, and we’re pretty sure that Craig is not going to be able to give himself over to that sort of thing. And in fact, Craig is unhappy for a lot of Carnet. He counts the ways: he’s homesick, he misses his ex-girlfriend profoundly, she’s quite ill, he’s lonely, everything reminds him of her, he’s lonely, his hand hurts from so much drawing. Did we mention he’s lonely? His internal struggles spill out into the frames and pages of his notebook, enveloping them in fog of gloom. Morocco, near the beginning of the trip, is especially difficult, primarily because he doesn’t know anyone, doesn’t understand the culture very well and plunges into the worst melancholy of the trip.

Except that maybe we’ve read Blankets, and we’re pretty sure that Craig is not going to be able to give himself over to that sort of thing. And in fact, Craig is unhappy for a lot of Carnet. He counts the ways: he’s homesick, he misses his ex-girlfriend profoundly, she’s quite ill, he’s lonely, everything reminds him of her, he’s lonely, his hand hurts from so much drawing. Did we mention he’s lonely? His internal struggles spill out into the frames and pages of his notebook, enveloping them in fog of gloom. Morocco, near the beginning of the trip, is especially difficult, primarily because he doesn’t know anyone, doesn’t understand the culture very well and plunges into the worst melancholy of the trip.

By the time he returns to Europe, things start to lighten up. Some. Everything is more familiar. He eats great food. The pages feature more drawings of attractive women. He has conversations with interesting people, including his comic artist heroes. He sees relatively happy families in action. But his drawing hand REALLY hurts, enough to seek treatment, and despite the numbers of slender, attractive European women around him, he misses his ex. The commercial part of the comics business is difficult for him — the speaking, signing of books, conventions. And then he leaves, though by the end he’s getting to like it. Barcelona? Hard to argue.

Why is this relatively familiar story so engaging?

Several reasons come to mind — Thompson’s a likable character himself, he understands that a certain amount of his unhappiness is self-inflicted, we empathize with him as a character coming to grips with himself. And Carnet is beautiful — Thompson is an excellent artist. His lines are deft, he can reveal complex scenes, architecture, foliage and portraits with economy. He understands the power of suggestion. The drawings feel fresh, quickly sketched (they are), and when he employs comic book conventions, which he does frequently, they add to the sense of delight — the labels, the dialog bubbles, his “cartoony” depiction of himself. Throughout there’s the sense of “hand-made” and “care.”

Which means it “reads” as true. At the beginning of the notebook Thompson writes, “The stories, characters, and incidents in this publication are based on the personal experiences of the author, but should not necessarily be considered the truth with a capital “T”.” I take this seriously — Thompson is scrupulous about matters such as these. On his website recently, he explained in detail his drawing “program” for Carnet to someone who had asked whether or not it was a “true” sketchbook (the answer: basically, yes).

But I’m not sure what he means by his parsing of truth (or Truth). That there is fictional material in Carnet? I don’t think so. That he “dramatizes” some of the incidents, even some of his interior states of mind? This seems possible, I suppose, though I’d guess not. That he doesn’t trust his memory completely? Sure. Are all the quotes verbatim? That’s really hard to do: I bet not. In some deep sense does he allow the possibility that his sense of things might be incomplete or incorrect? Absolutely. Does he omit some of the Truth? Of course, for all kinds of reasons, I suspect, from ego preservation (though there are ample ego-destruction bits) to banality to avoidance of repetition to… any number of reasons (see Borges’ map that is the size and detail of the empire that is to be mapped).

Does Carnet tell us what Morocco is like? Of course not. It’s what Thompson found, singularly, in his state of mind. It’s a valuable description, though. We don’t doubt its truthfulness in the larger sense. Should you avoid Marrakesh because of what Thompson writes and draws? No, but you might try to avoid the central square, the medina, for much of your time there, and maybe you should take along a companion so you don’t feel lonely. The byplay between the internal (how Thompson is feeling, what he is thinking) and the external (what he is seeing) gives Carnet a lot of its tension. And in that tension, that friction, we get the heat of “truth” if not “Truth”.

Back to the nomenclature problem, which Thompson addresses almost directly in Carnet. In Toulouse, he is introduced to Blutch one of his favorite cartoonists. “We went out for beer and discussed comics — and about how “autobio comics” can mess with your real life. With his current work Blutch says, ‘There is nothing real, but everything is exact. … Just the juice of reality.'” Which is “fiction” in my book. But “autobio comics” — that’s a good category to remember. And it includes lots of other popular but non-Marvel, non-DC, comics guys, from Lynda Barry and Harvey Pekar and on to the present (not that Barry and Pekar aren’t part of the present!), artists who base their work on real events and characters from their past. We can debate whether we think any specific incident is literally true in its details, but we assume that they were lived that way, at least approximately, because the artist/writer is testifying that they were — if we decide the he or she is trustworthy.

The bare account of Guy Delisle of life in North Korea is personal but not so intimate as Thompson’s Carnet, and it moves us a step closer to journalism.

Guy Delisle

How empty is it?

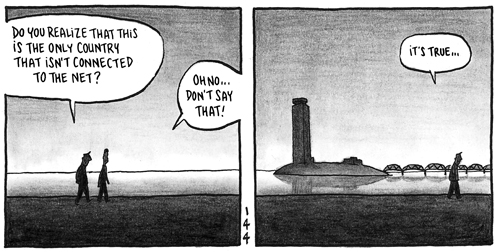

Like Carnet de Voyage, Pyongyang: a Journey in North Korea is a journal of a trip. In this case it’s Guy Delisle’s business trip to North Korea. Delisle, a French Canadian, worked for a French animation company, which farmed out big chunks of the actual animation to North Korea (Delisle says that Eastern European studios also get lots of this sort of work). Basically, the North Koreans take their cue from the the “key” drawings in a movement sequence and fill in the drawings between them. Delisle supervised their work.

But animation “experiences,” though informative (think about the whale rendering passages in Moby Dick, except shorter), don’t occupy many of the frames of Pyongyang. Instead, Delisle records the life he finds in North Korea. There is one very great difficulty to this: He must be accompanied everywhere he goes by a guide and translator. And he must stay in an almost empty hotel for foreigners, which is cut off from the rest of the city. So the book takes us on a series of excursions, some more impromptu than others, as Delisle attempts to get closer to the “real” Korea than the government wants him to get. If anyone has a complaint about loneliness, it’s Delisle, but he rarely mentions it. Instead, he works on his guides, trying to trick them into an admission of some kind or get them to take him somewhere off-limits. They seem pretty tolerant, even friendly in a distant sort of way, but they are NOT going to fall for Delisle’s tricks.

Given this tiny range of investigation, what do we learn? Quite a bit, actually. What immediately becomes apparent is the emptiness. Unlike the marketplaces in Morocco, teeming with beggars and grifters, Pyongyang seems abandoned in Delisle’s frames, only a skeleton crew left to mind it. The huge monuments to Kim Il-sung or Kim Jong-il are solitary, like Sphinxes in the desert. The streets have few cars, fewer pedestrians. Presumably there are markets, but we don’t visit them, so maybe not. Even the countryside, when we get there, seems de-populated. One of the primary affects of coercion and control at the North Korean level — human activity stops. And although his drawings are far less detailed than Thompson’s, Delisle recreates the static, deep-freeze environment, weird and exotic in its own way as Marrakesh.

Given this tiny range of investigation, what do we learn? Quite a bit, actually. What immediately becomes apparent is the emptiness. Unlike the marketplaces in Morocco, teeming with beggars and grifters, Pyongyang seems abandoned in Delisle’s frames, only a skeleton crew left to mind it. The huge monuments to Kim Il-sung or Kim Jong-il are solitary, like Sphinxes in the desert. The streets have few cars, fewer pedestrians. Presumably there are markets, but we don’t visit them, so maybe not. Even the countryside, when we get there, seems de-populated. One of the primary affects of coercion and control at the North Korean level — human activity stops. And although his drawings are far less detailed than Thompson’s, Delisle recreates the static, deep-freeze environment, weird and exotic in its own way as Marrakesh.

Stasis is an odd “topic” but it does make incidental events, like drinking too much with one’s guide and translator for example, seem dramatic. Melon at dinner? Time to celebrate… and then conclude that foreign delegations that the government wants to impress must be in the city. But “nothing” is going to happen. There’s no happy ending. Delisle puts in his two months. He packs up. He leaves. North Korea stays as he found it, though he HAS left a copy of 1984 with one of the translators, a bottle of Hennessy VSOP for his guide and some paper airplanes he’s floated from his hotel room to the city below. But Delisle is skilled enough to pull you along anyway, the inquisitive mind set loose on a place that actively resists providing answers.

How to characterize it… a memoir, yes, but not as personal as Craig Thompson’s Carnet. We learn nothing about Delisle’s sex life (Thompson is more open about his) or his thinking about much of anything except for North Korea. But it’s still a personal account: “What I saw in North Korea,” with the emphasis on the I, even though we suspect that the experience of any foreigner is going to be similar if not identical. And as blank as Delisle himself remains, like North Korea, he reveals something of himself. So a personal report, yes, one that acknowledges its limitations, in fact one that turns out to be ABOUT its limitations.

If PyongyangWar’s End gets us to the heart of war journalism.

Joe Sacco

Extreme journalism (extremely good)

Both Craig Thompson (even in the looser diary format of Carnet de Voyage) and Guy Delisle follow comic book conventions. In Thompson’s work they show up in the idealized women, for example, the relative inexpressiveness of the faces and in the representation of himself as a Woody Allen kind of character usually underdrawn compared to the rest of the characters. Delisle’s Pyongyang reads even more like a comic — lots of frames per page, action (what there is!) moving along linearly, and his own self-depiction is VERY cartoony: none of the other characters is so unnaturalistic.

Sacco lives in a different world — War’s End: Profiles from Bosnia 1995-96 wants to demolish the acceptable boundaries of comics, the affect of most Sacco books. The subject matter is grimmer. The drawings act as though they want to spill off the page. Words can fill huge chunks of space. (There are moments in Carnet that resemble Sacco’s work: Thompson has cited Sacco as an influence.) I like the subversion and the obsession with getting it right: We interpret it immediately as “seriousness of purpose,” and I accept it as a reasonable account of what happened, especially the events that Sacco witnessed directly.

This isn’t Sacco’s best-known work on the war over the independence of Bosnia — that would be Safe Area Gorazde: The War in Eastern Bosnia 1992-95 (2000). War’s End was released in a hardback version in 2005, collecting two shorter pieces that appeared in the 1990s, Soba! and Christmas with Karadzic. Soba! is a profile of a chunky rocker/artist/soldier in the Bosnian Army. Much of the story is in the form of Soba’s recollections of fighting at the front (he dealt with mines, laying them and deactivating them). And then as peace approached, Sacco watched Soba attempt to make the transition from war to peace.

I have my doubts about Soba as a reliable narrator of his war experiences. Maybe Sacco tested his stories in various ways (talking to his friends, for example), but he doesn’t tell us that. We are intended to accept intense images of war as fact, when we know they are reported recreations that couldn’t be as dense with data as Sacco’s drawings are. The frame of Soba clutching a tree root as his hillside position is shelled , while men around him are dying and the sky is swirled and illuminated by the bombardment, is incredibly powerful, but was Soba’s automatic rifle leaning just so against the root? It’s hard to believe that Sacco KNOWS that. On the other hand Soba’s account deserves a hearing, whether we think it’s absolutely factual or not, and it’s not outlandish by any means.

Once we get to Soba in peacetime, though, and Sacco himself is on hand to observe and record, that’s a different story. It’s utterly believable, down to the expressions on Soba’s face. Sacco himself appears in these frames, not a flattering picture, mainly just listening and watching, but his presence gets us back on solid reporting ground. And it’s actually more interesting than the war frames: Soba struggles to come to grips with the absence of war — how does he pick up his life, does he stay in Sarajevo or leave for Italy, can he overcome his jitters and his bravado, has he been rendered too crude for “normal” life? Sacco likes him, it’s apparent, BUT he can’t help but depict him at his worst (often in pursuit of women). It’s a brilliant portrait.

Christmas With Karadzic is about two journalists Sacco is hanging with and their attempt to interview the notorious head of the Bosnian Serbs, Radovan Karadzic, later indicted for war crimes. What does Sacco report: The cynicism of the reporters, their shaky representation of reality (trying to get gunfire on tape when it’s quiet, for example) and ultimately their success at getting a few minutes with Karadzic at a Christmas church service. But it’s still a sharp, speedy drive through dangerous territory. The surprise? That Sacco himself can’t work up any outrage at Karadzic, a man who represents atrocities that he loathes. Sacco’s sensibility has changed; not his politics, but his capacity to respond. The writer testifies to the transformative nature of what he has witnessed, and it spills over to the other characters, who, we reason, have adapted to the war to a similar degree, personalities evolving, deteriorating, defenses erected, hardening, coarsening, like Soba. Sacco takes us to the extremities of this bitter little Balkan conflict — the 10,000 dead in Sarajevo alone, the life and lives blown apart — for both the dead and the living.

Sacco’s drawing is both expressionistic (look at the dogs on cover of War’s End) and unusually detailed, and he gets the full impact of both. We get the feeling from his dark, kinetic images and the testimony to his accuracy from the details. It’s difficult for us to really examine, to read, to interpret the drawings; we just don’t want to go there with Sacco. If Soba is a sympathetic character, if Sacco himself becomes numb to Karadzic, falls into the aggressive cynicism of the journalists around him, then we should consider ourselves warned.

Sacco’s drawing is both expressionistic (look at the dogs on cover of War’s End) and unusually detailed, and he gets the full impact of both. We get the feeling from his dark, kinetic images and the testimony to his accuracy from the details. It’s difficult for us to really examine, to read, to interpret the drawings; we just don’t want to go there with Sacco. If Soba is a sympathetic character, if Sacco himself becomes numb to Karadzic, falls into the aggressive cynicism of the journalists around him, then we should consider ourselves warned.

Journalism can’t do more than this.

The only problem with Sacco’s graphic journalism is how time consuming it is; it becomes graphic history as he labors at the drawing table. But that’s a fine category, too. And when we consider Sacco, Thompson and Delisle together, we embrace their variety, the way they span possible categories, the way they define themselves as they go along. No, “graphic novel” does not contain them; they argue for a much larger set of names. So call them what you like; call them what they are.

Sacco, Thompson and Delisle bring intelligence and skill to their subjects, and even better they bring intensity that borders on the obsessive. Long-form graphic projects demand that. And ultimately, that in itself testifies to their seriousness of purpose and lends their non-fiction, however we choose to describe it, a deep credibility — exactly what non-fiction yearns for.