High above the windy hollow of the Columbia River Gorge, Sitting Bull and Geronimo and Gen. George Armstrong Custer seem right at home.

High above the windy hollow of the Columbia River Gorge, Sitting Bull and Geronimo and Gen. George Armstrong Custer seem right at home.

And Andy Warhol? Surprisingly, him, too.

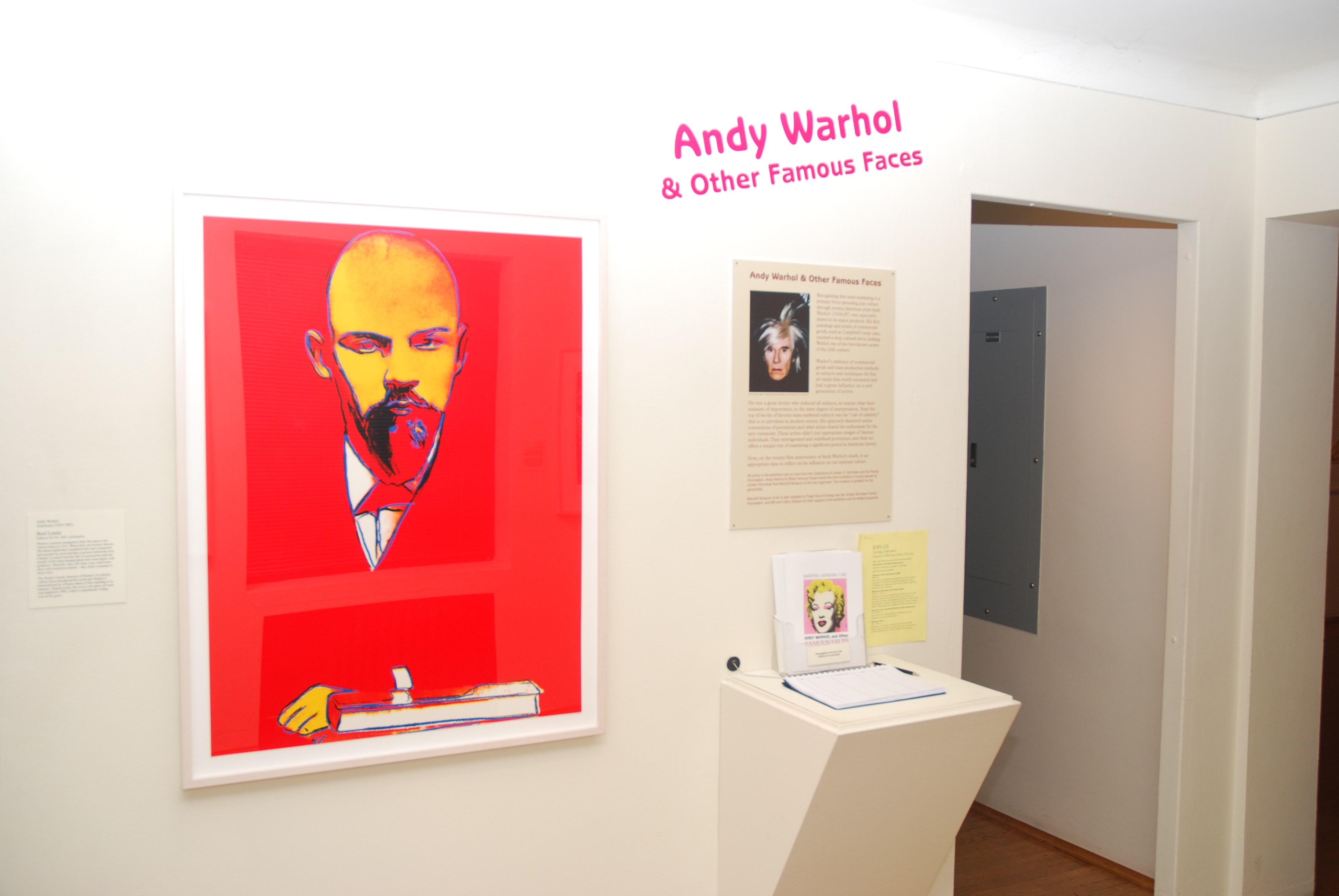

Warhol, the epitome of a certain sort of New York sophistication — a self-created phenomenon of the 20th century, pointing the way to the 21st — is the focus of a new show in the upper galleries of the Maryhill Museum of Art, “Andy Warhol and Other Famous Faces,” assembled from the contemporary print collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and his Family Foundation.

The exhibit, with images mostly by Warhol plus a sprinkling of supporting pieces by the likes of Robert Rauschenberg, Red Grooms, Chuck Close, Jasper Johns and Jeff Koons, proves once again what has become a mass-culture commonplace: In a world of celebrity-soaked informational sameness, we are all from Manhattan, all from Iowa, all from the sparse deserts of the West. Red state or blue, right wing or left, Elvis and Marilyn and Campbell’s Tomato Soup have brought us together and made us alike — or at least, given us the same pop-cultural preoccupations.

Maryhill, one of the unlikeliest of American art museums, sits in a concrete castle on a high bluff on the Washington side of the Columbia River, about 100 miles east of Portland and well on the way to desert country: It’s practice territory for the Middle of Nowhere. The fortress was built as his residence by the visionary road engineer and agricultural utopian Sam Hill. (His Stonehenge replica, a World Wat I memorial, is nearby, and the next time you head for Vancouver, British Columbia, you should stop on the border at Peace Arch Park to take in another of his monuments, the International Peace Arch, which sits with one foot in Blaine, Washington, and the other in Surrey on the Canadian side. Both monuments are as clean-lined and populist as any of Warhol’s works, and a good deal more interactive.)

Hill’s mansion was transformed into a museum by three of his high-powered women friends, including Marie, Queen of Romania, who was related to the royal houses of both England and Russia. As a result its collections are heavy in memorabilia of the good queen’s life (including some furniture she designed), plus objects related to another benefactress, the great dancer Loie Fuller; a goodly amount of Rodin; a good sampling of Native American art; many fine Russian Orthodox icons; quirky attractions such as the French high-fashion stage scenes of Theatre de la Mode (even Jean Cocteau took part in this immediately post-World War II artistic attempt to give French haute couture a sorely needed economic kick-start); and an amusing, sometimes amazing sampling of international chess sets.

Hill’s mansion was transformed into a museum by three of his high-powered women friends, including Marie, Queen of Romania, who was related to the royal houses of both England and Russia. As a result its collections are heavy in memorabilia of the good queen’s life (including some furniture she designed), plus objects related to another benefactress, the great dancer Loie Fuller; a goodly amount of Rodin; a good sampling of Native American art; many fine Russian Orthodox icons; quirky attractions such as the French high-fashion stage scenes of Theatre de la Mode (even Jean Cocteau took part in this immediately post-World War II artistic attempt to give French haute couture a sorely needed economic kick-start); and an amusing, sometimes amazing sampling of international chess sets.

But the museum’s permanent fine-art holdings are largely romantic landscape, plus Victorian and American realist paintings. As a result, it relies largely on temporary shows for things a little closer to modern times.

This is the third exhibit that Maryhill has presented from the Schnitzer collections, and it’s proven a fruitful partnership. This end of the Gorge is arid, close to cowboy country, and Maryhill is frequented heavily by visitors who don’t often go to art museums. That makes Warhol, the only partly ironic celebrator of the merging of high and low culture, an unusual yet in some ways an ideal fit for Maryhill’s ventures into near-contemporary waters.

Sitting Bull and Custer, principles in the 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn, sit cheek by jowl in Warhol’s screenprint portraits from 1986, and the contrast is striking: Sitting Bull forthright in a blue face with bold yellow outlines, Custer a frontier dandy with bushy moustache, averted eyes and receding chin. In the next gallery, Geronimo — paired with Warhol’s screenprint rendition of a Coast Salish ornamental mask — is strong, still and grim-lined, with a fierce gravity that seems to weigh heavily on him and flatten his skull.

These icons of the American West coexist easily with other, more famous faces: Marilyn Monroe, of course (Warhol’s bright-lipped portrait is one of the world’s most familiar images), Queen Elizabeth II of England, Jimmy Carter, in a 1977 portrait from around the time of his inauguration. Relaxing in a red sweater from Mr. Rogers’ neighborhood, Carter and his huge toothy smile seem a little like a leisure suit. He seems a good, maybe slightly goofy man, not stylish but smart and generous and capable, and looking at the print you wonder: Why was this president so reviled? (Compare him to “Red Lenin,” Warhol’s spare but probing 1987 portrait of the Russian leader: cartoonish lines, tiny reproduction dots that indicate this is a mass medium for a man in control of the masses; the beard, the sharp eyes, the high forehead, and red — red everywhere, a wash, a sea, a swallow, a spilling of red.)

These faces are so familiar that it’s easy to give them a glance and move right along, as if nothing is to be gained by lingering. But in fact, in almost every case Warhol reveals something hidden, something hinted, beneath the easy surface. Or, given the celebrity of his subjects, do we provide the depth ourselves? This relationship isn’t as simple as it seems. Warhol opens windows. What we see is up to us — but he’s framed the view.

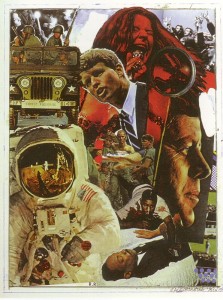

The exhibit gives shape to its vision of Warhol partly through the works of its other artists, who are like Warhol but not the same. There is Rauschenberg’s political sensibility in his famous 1970 screenprint “Signs,” inspired by the lift-off two years earlier of Apollo 11: images of Bobby Kennedy, JFK, Janis Joplin (the artist and singer were both born in Port Arthur, Texas), Martin Luther King Jr. lying in state, an American moonwalker, G.I.s at war, a black man lying in a pool of blood. It’s a world shaken by a barrage of cataclysmic events — and right next to it is Warhol’s equally famous, intimate portrait of Jacqueline Onassis Kennedy — completed in 1966 after her husband’s assassination — smiling and almost unbearably serene in her pillbox hat. As in so many of Warhol’s portraits, his vision of Jackie carries a striking sense of innocence, touched by a vulnerability that seems purely personal. See it again in his 1978 portrait of Liza Minnelli: doe eyes, red-gloss lips, a shag of dark hair and a sadness in the face behind the geisha mask. Warhol’s sense of politics and history is a matter of famous people caught in the headlights of their fame.

The exhibit gives shape to its vision of Warhol partly through the works of its other artists, who are like Warhol but not the same. There is Rauschenberg’s political sensibility in his famous 1970 screenprint “Signs,” inspired by the lift-off two years earlier of Apollo 11: images of Bobby Kennedy, JFK, Janis Joplin (the artist and singer were both born in Port Arthur, Texas), Martin Luther King Jr. lying in state, an American moonwalker, G.I.s at war, a black man lying in a pool of blood. It’s a world shaken by a barrage of cataclysmic events — and right next to it is Warhol’s equally famous, intimate portrait of Jacqueline Onassis Kennedy — completed in 1966 after her husband’s assassination — smiling and almost unbearably serene in her pillbox hat. As in so many of Warhol’s portraits, his vision of Jackie carries a striking sense of innocence, touched by a vulnerability that seems purely personal. See it again in his 1978 portrait of Liza Minnelli: doe eyes, red-gloss lips, a shag of dark hair and a sadness in the face behind the geisha mask. Warhol’s sense of politics and history is a matter of famous people caught in the headlights of their fame.

Red Grooms’ cartoonish portraits — Chuck Berry; skinny Elvis in front of a gleaming Cadillac, with Graceland and a beehived Priscilla and puppy in the background; a 3-D Charlie Chaplin cutout, kicking out his leg as the Little Tramp — are lighter and more optimistic. Jeff Koons’ hyperrealistic portrait of Michael Jackson and his monkey Bubbles — golden and shiny like fine porcelain — is cold and creepy in a way that Warhol’s art never is. Takashi Murakami’s 2004 “White DOB,” a ubiquitous animated character in Japan, is playful and frankly inconsequential in a way that even Warhol’s soup cans and Brillo pads aren’t: After all, those images of the everyday industrial object signaled a turning point in the idea of what the subject of art could be.

Celebrity is nothing new in the history of art, but mass reproduction and mass audiences are. Was the response different when Hans Holbein the Younger was painting Henry VIII and the aristocracy of England? I don’t know (although certainly Holbein was more aware of political, in addition to charismatic, power). But the audience was smaller. And Warhol knew how to play his larger audience, to vary things and keep the interest coming. The Maryhill show contains a single soup can image, from 1978, 16 years after his original 32 soup cans lit the art world’s kitchen on fire. This one’s small, quiet, black and white. It says: Look again. I’m not the same.

Celebrity is nothing new in the history of art, but mass reproduction and mass audiences are. Was the response different when Hans Holbein the Younger was painting Henry VIII and the aristocracy of England? I don’t know (although certainly Holbein was more aware of political, in addition to charismatic, power). But the audience was smaller. And Warhol knew how to play his larger audience, to vary things and keep the interest coming. The Maryhill show contains a single soup can image, from 1978, 16 years after his original 32 soup cans lit the art world’s kitchen on fire. This one’s small, quiet, black and white. It says: Look again. I’m not the same.

What were Warhol and company up to? What does it mean to erase the line between high and low art? In an age of mass production and mass communication (and a time when the spread of democracy raised the possibility that the common man and woman would become more important forces than the financial and cultural and intellectual elites) they believed that what was important was in front of everyone’s eyes. If people used it, adopted it, enjoyed it, it was important. If our culture was obsessed with celebrity, celebrity became of vital interest. Elvis was more important than Toscanini because — well, because he was. Coca-Cola. Campbell’s Soup. Liza. The Beatles. All peerless images, all the same. Reproduction and celebrity are the great levelers.

Of course, Warhol’s secret was that he so often showed more than the image, especially in his portraits: Like all great artists, he gave hints of essence and mortality. And this show underscores that, even with relatively large print runs, and even with Warhol’s position as a brilliant public-relations guy for mass images, his prints are vastly better seen in their original form than in magazine or postcard or online reproductions. Size and texture and the trueness of color are essential: They are, finally, works of art, not advertising images that can blow up or down from a magazine page to a billboard.

Intriguingly, for all his apparent democratic impulse, Warhol might well mark a breaking point between the world of art, which has become more and more esoteric, and the world of average citizens, who whatever they knew or didn’t know about it, seemed to hold art to a higher purpose than some of the artists themselves. Warhol’s art was open enough that it could be interpreted in many ways, not all of them especially complimentary to the man and woman on the street — people who, a few decades earlier, might look at a John Marin or Edward Hopper or even a Picasso or Dali and feel a kinship. To Warhol they might say, “Ah, yes, soup; he sees the importance and comfort of everyday sustenance.” Or, “Ah, yes, commerce: It makes the world go ’round.” Or, “This is what he thinks of us? We’re nothing but consumers? Well, that’s reductive.”

Intriguingly, for all his apparent democratic impulse, Warhol might well mark a breaking point between the world of art, which has become more and more esoteric, and the world of average citizens, who whatever they knew or didn’t know about it, seemed to hold art to a higher purpose than some of the artists themselves. Warhol’s art was open enough that it could be interpreted in many ways, not all of them especially complimentary to the man and woman on the street — people who, a few decades earlier, might look at a John Marin or Edward Hopper or even a Picasso or Dali and feel a kinship. To Warhol they might say, “Ah, yes, soup; he sees the importance and comfort of everyday sustenance.” Or, “Ah, yes, commerce: It makes the world go ’round.” Or, “This is what he thinks of us? We’re nothing but consumers? Well, that’s reductive.”

What was liberating for some was alienating for others, and ultimately fracturing to the sense of a common culture, even as it celebrated the commonality of mass communication. Yes, art was everywhere — and ironically, it was becoming more selective. After Warhol, the democratization of the art world became (if it had ever really been anything else) a democracy of the elite.

Andy Warhol and Other Famous Faces continues through Nov. 15, 2008, at the Maryhill Museum of Art, 35 Maryhill Museum Drive, Goldendale, Wash., just west of U.S. 97.

Hours are 9 a.m.-5 p.m. daily. Admission: $7; seniors $6; ages 6-16, $2; members free Phone: 509-773-3733. Web: www.maryhilllmuseum.org

————————————

A version of this story first appeared in the A&E section of The Oregonian on Friday, Aug. 8, 2008.