“Surrealism and Painting” Max Ernst (1942)

I celebrated Scatter birthday by revisiting the Menil Collection in Houston, the source for my posts last year on the extraordinary art collection amassed by two Europeans, John and Dominique de Menil, who brought their oil business and modern art collection to America at the beginning of World War II. Located in a park-like complex that is surrounded by a neighborhood of modest bungalows, the Collection of more than 16,000 pieces includes a gallery devoted to Surrealism and offers individual shows, such as last year’s idiosyncratic “How Artist’s Draw,” curated by Bernice Rose.

Last week I spent two days at the Menil, most of it wandering through the gallery housing “Max Ernst in the Garden of Nymph Ancolie,†then in its last two days. The show focused mostly on the evolution of Max Ernst’s themes and motifs between the two World Wars, culminating with a view of a huge (nearly 14 x 18 feet) oil on plaster mural he produced for a Zurich nightclub, which has been transferred to plywood panels and restored.

Surrealism and Ernst are the Collection’s core. The de Menils met Max Ernst (1891-1976) in Europe before World War II and became unalterably infected with his Surrealist vision. The show included a new film about the installation of a 1973 Ernst exhibit at nearby Rice University, supervised by Dominique de Menil. The film, “Max Ernst Hanging,†was produced by Francois de Menil and John de Menil, son and grandson of the de Menils, and features vintage black and white footage of Dominique de Menil organizing the show, as well as incredible coverage of Ernst, then in his early eighties, walking through the space while the exhibit is being hung, looking at pieces he hadn’t seen in years, and then mingling with Houston’s art patrons during the opening. Many of the pieces in the 1973 exhibit were on view in the current show. (Olga’s Gallery is a great place to get a quick look at a cross-section of Ernst’s work.) The experience sparked a few reflections.

Surrealism and Ernst are the Collection’s core. The de Menils met Max Ernst (1891-1976) in Europe before World War II and became unalterably infected with his Surrealist vision. The show included a new film about the installation of a 1973 Ernst exhibit at nearby Rice University, supervised by Dominique de Menil. The film, “Max Ernst Hanging,†was produced by Francois de Menil and John de Menil, son and grandson of the de Menils, and features vintage black and white footage of Dominique de Menil organizing the show, as well as incredible coverage of Ernst, then in his early eighties, walking through the space while the exhibit is being hung, looking at pieces he hadn’t seen in years, and then mingling with Houston’s art patrons during the opening. Many of the pieces in the 1973 exhibit were on view in the current show. (Olga’s Gallery is a great place to get a quick look at a cross-section of Ernst’s work.) The experience sparked a few reflections.

“What kind of bird are you?†(A question from a patron at the 1973 opening in “Max Ernst Hanging.â€) A good question. Ernst and his work are filled with birds, so much so that the painter adopted an alter-ego, “Loplop,†a phoenix-like, anthropomorphic bird that is at once image and observer in his work, and appeared again and again in his paintings and sculpture. Birds that are cut-out drawings or photographs used in collages, dotted-line or cartoonish birds in cages lightly painted on the surface of otherwise detailed paintings, sculptured birds, and strange biomorphic creatures that share bird and human and even vegetal and insect forms and characteristics. At times the birds seem trapped and isolated, at other times spiritual and free, and then, as in, “Surrealism and Painting,†shown above, the bird-human form – is it one figure or are there three? – suggesting an almost sentimental notion of family. It is serene, secure and a bit claustrophobic. But birds. Birds everywhere.

“A single point of rock, peak of a mountain range, one tooth set in the ancient jaw of a sunken world, projecting through the inconceivable vastness of the whole ocean – and how many miles from dry land.†(William Golding, Pincher Martin) Isn’t that the way art hits us at times, suddenly there in our sea of consciousness, vivid, pointed, recognizable on the surface, but suggesting something else vast, primal, uncharted beneath? And Surrealism clings to that notion as to a life raft adrift in life’s wide sea. The sense of alienation, the chance encounter with the people, places and objects (the chance of my reading the Golding book the night before I tripped into the Menil), the gaze seeking the face beneath the mask, the strata below the surface, the crack in the facade. And the deliberate search for the exotic, travel as a surrealist activity, especially the encounter with the primitive, and the now somewhat antiquated notion that the primitive observed is an earlier version or hidden layer of the observing self.

“Close your bodily eye, in order to see your picture with the mind’s eye.†An idea Ernst picked up from Caspar David Friedrich, one of the painters he admired. The eye confronts the elements of tradition but it is the inner eye, driven by the needs of the present, which transforms the work to show us things about the past we never expected. Ernst nurtured that inner eye, teased it, with versions of automatism, coincidence, chance. Ernst famously pioneered various automatist techniques: frottage, rubbing paper over floorboards and catching the random, suggestive image in the wood grain; grattage, scrapping paint from a textured surface to find unexpected, revelatory patterns; and decalcomania, pressing paint between two surfaces, leaving mottled, intricate patterns when the top layer is removed. The mind’s eye, aided by chance, moves the painted surface in a new direction.

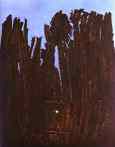

This accounts for the strangeness in Ernst’s paintings. The intricate patterns created by combining these techniques in the painted surface had me jotting metamorphosis, biomorphic, decay, calcification and my old aunt’s lace doilies as I peered closely at the surface of the paintings. The grainy look, the cauliflower, lace and snake-scale walls like crumbling jungle temples. The classically-sculpted human forms either emerging from or sinking into calcified vegetation. Creatures that mutate from one limb to another limb. The thick, impossible forests, painted collages of wood grain or serrated, fishboned, feathered images, or, what look to me like upended centipedes, like the trees in “Forest and Dove,” above. And landscapes that have been charred and mined or else chiseled with no-longer intelligible writing. In art book reproductions especially, it is difficult to distinguish the chance mark from the deliberate brush stroke; but difficult up close, too.

This accounts for the strangeness in Ernst’s paintings. The intricate patterns created by combining these techniques in the painted surface had me jotting metamorphosis, biomorphic, decay, calcification and my old aunt’s lace doilies as I peered closely at the surface of the paintings. The grainy look, the cauliflower, lace and snake-scale walls like crumbling jungle temples. The classically-sculpted human forms either emerging from or sinking into calcified vegetation. Creatures that mutate from one limb to another limb. The thick, impossible forests, painted collages of wood grain or serrated, fishboned, feathered images, or, what look to me like upended centipedes, like the trees in “Forest and Dove,” above. And landscapes that have been charred and mined or else chiseled with no-longer intelligible writing. In art book reproductions especially, it is difficult to distinguish the chance mark from the deliberate brush stroke; but difficult up close, too.

Fantastic, but certainly not fantasy. A painting such as “Europe After the Rain II,” at left, is not some other fully-imagined world precious and quaint, but a carefully orchestrated versions of this one. “Unnaturally natural†or “naturally unnaturalâ€? I penciled in my notes. There’s a wavering between nature and civilization in a lot of the paintings. A rigid tension between Nature and Civilization writ large at the far ends of the spectrum, but at the point of biomorphic merger, it is unclear that either holds the upper hand, though history suggests Nature will overwhelm in the end. Some of the most evocative texturing on Ernst’s oldest paintings is the result of the checked and cracked surface of the paint, and that despite careful, controlled-climate museum preservation and restoration.

Fantastic, but certainly not fantasy. A painting such as “Europe After the Rain II,” at left, is not some other fully-imagined world precious and quaint, but a carefully orchestrated versions of this one. “Unnaturally natural†or “naturally unnaturalâ€? I penciled in my notes. There’s a wavering between nature and civilization in a lot of the paintings. A rigid tension between Nature and Civilization writ large at the far ends of the spectrum, but at the point of biomorphic merger, it is unclear that either holds the upper hand, though history suggests Nature will overwhelm in the end. Some of the most evocative texturing on Ernst’s oldest paintings is the result of the checked and cracked surface of the paint, and that despite careful, controlled-climate museum preservation and restoration.

“Max Ernst died the 1st of August, 1914,†Ernst wrote, after his service in the German army during World War I. We cannot measure fully in personal terms the effect of that war on Dada, Surrealism and Futurism and other art or literary movements of the time, and we often forget how many artists and writers were involved in that war in a way that they are not now in our own time of “small war on the heels of small / war – until the end of time” (Robert Lowell, “Waking Early Sunday Morningâ€). Photos of the destroyed European landscape after World War I provide a vivid representation of an Ernst painting in another key. Compare Ernst’s painting “Europe After the Rain II,” above, with the photo of what remained of Ypres in 1917.

“Max Ernst died the 1st of August, 1914,†Ernst wrote, after his service in the German army during World War I. We cannot measure fully in personal terms the effect of that war on Dada, Surrealism and Futurism and other art or literary movements of the time, and we often forget how many artists and writers were involved in that war in a way that they are not now in our own time of “small war on the heels of small / war – until the end of time” (Robert Lowell, “Waking Early Sunday Morningâ€). Photos of the destroyed European landscape after World War I provide a vivid representation of an Ernst painting in another key. Compare Ernst’s painting “Europe After the Rain II,” above, with the photo of what remained of Ypres in 1917.

Imagination and memory are braided, then the whole is frottaged and grattaged, layer after layer, all the way down to the bone.

Paintings from Olga’s Gallery, www.abcgallery.com:

“Surrealism and P[ainting” (1942), Private collection.

“Forest and Dove” (1927), Tate Gallery, London.

“Europe After the Rain II” (1940-42), Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford CT.

Photo of Ernst, Max Ernst: Life and Work, by Werner Spies